When watching The Women of Summer, one of the most surprising things was learning about how Bryn Mawr was on the forefront of a progressive social movement. I was especially shocked when one alum of the Summer School mentioned how a Philadelphia newspaper had claimed Bryn Mawr was a “hotbed of radicalism”, since that isn’t how I perceive Bryn Mawr’s reputation at all.

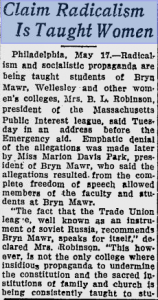

I googled Bryn Mawr and “hotbed of radicalism” to see if I could quickly find the article that the women had referenced. I didn’t find that one in particular, but I did find this article from the Evening Independent of St. Petersburg, Florida from May 17th, 1923, which I’ve screen capped below:

(found on Google News, who made it incredibly easy to find a relevant newspaper headline from 93 years ago online.)

The entire story of the the Summer School for Women Workers in Industry was fascinating, but I was especially interested in the way that it was understood with its political context. The Evening Independent article doesn’t specifically mention the Summer School, but it does hint at Bryn Mawr’s progressive reputation in the 20s and fears about union organizing. the claim of a direct connection between Bryn Mawr and Soviet Russia through the Trade Union League seems ridiculous, but it’s fascinating to think that the Summer School was radical enough to warrant that type of publicity.

Both the quote from Women of Summer and this article mention how Bryn Mawr publicly denied allegations of radicalism. The woman interviewed in the film mentioned how the school administration was angry about the “hotbed of radicalism” headline, and this article quotes a response from Marion Davis Park. Although Bryn Mawr may have been on the cutting edge, their public responses also show the way that the school was still invested in maintaining a reputation that was not tied to radicalism. The school’s response is another integral part of the story, which speaks to the various voices within the school as well as the potential difference between private goals and public image.