In Of angels, doves and oral history by Erin Bernard, he says, “How can we grapple with our own aesthetic intentions and the needs of our community relations?” Which made me think about a conversation I had about the relationship between artists and cultural appropriation, which was prompted by the picture below.

The person I was having the conversation with was struggling with the idea of cultural appropriation being a bad thing in the context of art. She thought it was a shame that there were so many beautiful things in the world that artists should be able to use. She asked if an artist donated money to a cause relevant to what that artist was interested in, would it then be appropriate to appropriate their culture? My own personal belief is that the idea that the artist’s desire for a certain aesthetic over the legitimization that objects and symbols in culture have more value and importance than an outsider may know, comes from a misunderstanding of power and privilege. Which leads me to these pictures:

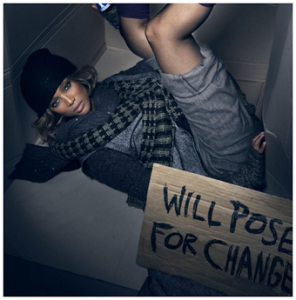

The first one is Tyra Banks from an America’s Next Top Model photo shoot, and the next is from a photo shoot that Kylie Jenner did for a magazine. Why they thought these photos would be appropriate, I don’t know. And though I doubt Kylie and Tyra were trying to make art that would for the purpose of preserving public history, I think this is a gross reminder that as artists entering somebody else’s community, there can be serious damage done if there is no care to do the art ethically and with respect and understanding. I believe Hayden talks about acknowledging power and structural inequality, but I believe the methods he speaks of, like body memory, can sometimes be used in questionable ways. Added with Schiavo’s idea of how to make meaning in museums, a lot of things could happen.

I had difficulties adding pictures to this post, so I had a friend help me out. After seeing the second picture of Kylie, she told me about a museum that she went to where one of the special exhibits they hosted was about disability. In order to see the exhibit, you had to be in a wheelchair. There were a lot of winding paths to take, and the idea was you would see how hard it was to be in a wheelchair. But, my friend pointed out, will that experience really show you how it’s like to be in a wheelchair for the rest of your life? Does sleeping outside for one night show you what it’s like to be homeless? (Tyra said she was inspired to do her photo shoot after she spent one night outside to see what it was like to be homeless. She says she now really understands.) However it is possible that experiences like these create more awareness, which is desirable. But is it worth it?

A quote from Hayden, “Citizens surveyed about history will often speak disparagingly of memorized dates, great men, “boring stuff from school” disconnected from their own lives, families, neighborhoods, and work.”, pg 45-46. Which made me write in the margins, “Is history that doesn’t serve to help people understand their own lives and lived experiences worthless?” Which brings us back to the question, who are we making history for? Is it for the people who are able to walk around exhibits and need to “experience” “oppression” in order to learn, or is if for the people who already know what that oppression feels like?

I’m pretty sure Hayden and Bernard would agree with me, so I don’t really know who I’m arguing against. But here we are.

“Is history that doesn’t serve to help people understand their own lives and lived experiences worthless?” “Who are we making history for?” These are great questions, and I read them in the context of many posts this week, but especially the conversation on Angela’s post, around the burdens of doing/sharing one’s community’s histories. “I want history to be remembered through the voices of those living in it, but I don’t want the pressure to be on the people to recount the events, especially when so many other things are going on,” Angela argues, and I see this concern in many public history discourses today.

You might be interested in a piece that ran in the New York Times this weekend, on the new National Museum of African American History and Culture: at least I keep wondering about national museums/memorials and local/community projects, stories, and feelings.

* editorial note: Erin Bernard (line 1) is a she!

@ Gabby- yes!!!!! thank you!