I recently had the opportunity to go to “Re(covering) Ourstories,” an event/exhibit/panel on the “bathroom graffiti controversy of 1988” that occurred at Bryn Mawr College. Organized by a Bryn Mawr student, the event examined an incident that happened on campus close to 30 years ago. In 1988, students at Bryn Mawr noticed that their bathrooms had been graffitied with insults and slurs hurled towards minorities on campus, particularly people of color and LGBTQ people. Amidst heightened racial and sexual tensions on campus due to elevated anonymous threats being delivered to students in addition to the recent death of a beloved classmate, a group of BMC students decided that they would reclaim the bathrooms and cover up the harmful graffiti in them with their own positive affirmations for one another. Since the administration had known about the slurs in the bathroom for weeks and had failed to do anything about it, the students (who had confined their activist graffiti to one bathroom) believed that their graffiti would be there for at least a week. However, the administration caught wind of the graffiti almost immediately after it was first put on display and decided that something had to be done to get rid of it, stat. With so many queer-positive expressions and concerns displayed within the graffiti, the administration feared that the public world of Bryn Mawr (which was still trying to figure out how to handle its LGBTQ identity amidst its more conservative alums/history) was colliding with the private world of Bryn Mawr. In haste, the administration decided that the new graffiti needed to be covered, and in a scene that could come out of a dark comedy, the President of the College enlisted the President of SGA to help her paint over the graffiti during the evening. What came next is history.

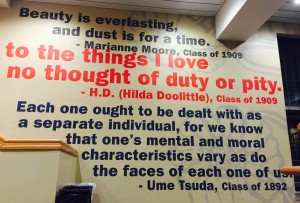

There are so many components to the bathroom graffiti story that make it a multifaceted and complex subject as a whole in Bryn Mawr’s history. It’s necessary to know the context of LGBTQ identities at the College during the time to understand the admin’s decision, in addition to the climate of the campus in general. I was impressed with the presentation of the exhibit and was glad that photographs of the positive graffiti had been taken before they were painted over. I particularly appreciated the panel that was set up to help get all of the points of view concerning the event on the table. This included one of the people who spray painted the positive graffiti, the then editor of the College News, and the then President of SGA. Without the points of views, the exhibit would’ve still been fascinating but it also would’ve missed a crucial, human element that made the event such a representative part of Bryn Mawr’s history during the time.

This exhibit is a real life example of the importance of documenting and archiving history at Bryn Mawr for the sake of institutional as well as activist memory. I had no idea about the bathroom graffiti incident until I came to the event and it intrigued me how easy it was to cover the event up and let it fade as the turnover of students occurred. This could very well happen with events that have occurred on campus within the last couple of years as well. The only thing that might prevent this, is the active presence of the Internet and social media to keep reminding and informing new people when others have forgotten. However, even the Internet is fallible, and things can be deleted from there too. Which makes the case that archiving, at the moment, from multiple perspectives/points of views is not only important but crucial to maintaining memory, and by attachment, history.