As I was reading both Filene’s “Passionate Histories: ‘Outsider’ History-Makers and What They Teach Us,” and Trouillot’s Silencing the Past, I kept thinking about my role as one of the editors of the college news and how important and frustrating that work is. Last semester, when Bryn Mawr students were posting their opinions about race at Bryn Mawr on Yik Yak, I felt immense pressure to publish the posts, which Trouillot would call the “materiality of the first moment” (29). At the same time, I knew I couldn’t just publish the posts, because while it would be preserving the opinions, it wouldn’t feel right to present them without any commentary or interpretation. While I agreed with Trouillot that these moments of silencing–the immediate sources, how to archive them, and construct a narrative–are crucial for the creation of history, in reality these all happen in an instant. I felt so much pressure in that week to record and save what everyone was saying, and construct a narrative. In the end, we printed only a few posts from Yik Yak because we had space limitations, and I wanted to prioritize student response to the Yik Yaks, rather than the posts themselves.

The events of those two weeks were almost impossible to construct a narrative out of, because there were so many different incidents and movements all happening at the same time. If I were to break up the events by space I would say that they key action-spaces were:

- Radnor & Radnor Halloween

- The ECC Library, kitchen, and common room

- Campus Safety

- Yik Yak

- The Campus Center & SGA meetings

- Thomas Great Hall

The organization of power was radically different in each of these spaces. As I sat in each of these rooms, I was shocked that hardly anyone cared to participate in recording what was happening in the newspaper. No matter how many times I asked for help or offered to print things in the paper, the most that people did was listen politely. I don’t think this is anyone’s fault, or say this to complain about my peers, but just to say that I was baffled at how I felt like the only person in the room who understood that the newspaper was a powerful tool for recording and constructing a narrative.

I remember one of the weirdest moments of those weeks was when I was in the ECC Library, and students were planning to occupy Campus Safety, and one student recommended that they have someone from the college news present. Then, another student said, “Are we sure we want that? You know how the news can change things.” I felt like I had failed my peers if they didn’t know that they were the ones making the news. They were the ones who had the power to tell their own story. That’s the beauty of this feminist newsjournal, is that we make it our mission to prioritize voices that have been undervalued and silenced.

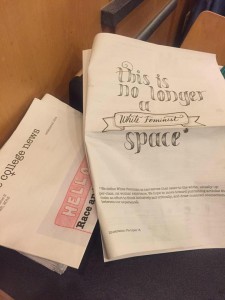

In the end, we published the “Race & Erasure” issue and got a great response from administrators, faculty and students. I’m skipping ahead in the story, but I think that the reason why it was so popular was because it was so timely, and because the students who wrote and submitted did a beautiful job of speaking out of their lived experience, as Filene writes about. Further, I think that having the paper come out then, and seeing the Yik Yak posts, along with a timeline of events going back a few years, created, as Filene writes, “a conversation, a civic dialogue” (26). I am endlessly fascinated with the college news as a space, and it’s unique power.

Even though we received a lot of positive feedback, I know that things fell through the cracks, and that we didn’t tell the whole story. Every issue I’m scared that someone won’t feel connected to the paper, and I really feel for historians, because I feel like at the end of the day, all they want is to tell a good story, and tell it right.