While I agreed with much of Erika Doss’ “Memorial Mania”, I was frustrated at her discussion of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Monument, specifically her dismissal of disability activists’ demands that the monument publicly acknowledge Roosevelt’s disability by showing him using a wheelchair. Although Doss seemed, in other sections, sensitive to reasons why different marginalized groups might demand representation, she seemed outright dismissive of the disability activists who advocated for a statue of Roosevelt using a wheelchair, saying things like, “disability activists… insisted that Roosevelt’s memorial more blatantly commemorate their own interests” (35-36), and quoting another scholar as saying, “Yet, Schudson cautions, rights consciousness also “legitimates individual and group egoism and emphasizes at every turn the individual, self-gratification over self-discipline, the economic over the moral, the short term over the long term, the personal over the social”” (37). I agree that demands for representation of individuals from different groups are rooted in identity politics and fail to address structural discrimination or create radical change–as Mason B. Williams says in “The Crumbling Monuments of the Age of Marble”, “Discussing individuals and (where warranted) removing names is good—but it is just a start. The crucial next step is to rethink and reinvent the ways the nation commemorates.” However, being so completely dismissive of a marginalized group’s demand for representation, and going so far as to imply that it’s self-gratifying, ignores the importance of representation for communities so often denied it. Representation is a form of individual empowerment for those who need to be able to look at the world and see people like them represented and celebrated, and a way of challenging larger discourses that invisibilize the experiences of marginalized peoples. In some cases, representation, by raising awareness of a marginalized group’s existence and breaking down stereotypes about them, can even start conversations that lead to more radical change in the future. Of course how representation is done matters, and representation alone is not the answer. But dismissing representation of marginalized groups as a form of self-gratification looks quite similar to arguing that only the voices and narratives of the privileged and powerful deserve to be heard, and I can’t see how that’s a way toward radical change at all.

Category Archives: Reading reflection

Historical Commemoration and the Present

“Its [the Age of Marble’s focus on statues of prominent politicians] key concerns lay elsewhere: in asserting shared values at a moment when the United States was torn by the legacy of the Civil War and Reconstruction” — Mason B. Williams, The Crumbling Monuments of the Age of Marble for The Atlantic.

This particular line got me thinking about the place that such monuments hold in society: Are they physical structures meant to commemorate past achievements, honor historical moments, as one would think? Or do they hold a far more present purpose?

Here, Williams argues that the purpose of statues, plaques, and structures named in honor of historical actors (almost exclusively old white politicians) were not entirely, if at all, meant to earmark the past. Public history has a reason for being that is intrinsically rooted in the present. Such structures can be used to remind warring groups of a shared goal, to honor values that are lacking in the present, to draw communities together, or to champion a moral, ethical, social, or other such cause. The naming of the Enid Cook dorm building can be seen in this same light: The Bryn Mawr community was (and still is) reeling from various attacks on the campus’ black community. Most disturbingly, at least to me, were the administrative movements to close down, change, and redesignate spaces reserved for the use of, and cherished by, the PoC community at Bryn Mawr. While many other measures were taken to rectify this issue and resolve the matter, the naming of the Enid Cook Center can be seen as a part of this resolution. It honors the black history at Bryn Mawr in a very public and very traditional way. It serves the purposes of preserving and honoring history, often seen as the reason for such monuments and dedications, while also serving the public (read: campus) need for resolution, rectification, and remembrance.

Similarly, the destruction of such monuments and the rededication of buildings to remove the reference to a now-unacceptable practice or worldview serves much the same purpose: championing the causes and healing the wounds of the present. Wiping Wilson’s name from Princeton’s systems and buildings would not change the historical record. It would not make his stance, so widely accepted in his time and so vilified in the present, any different. It does, however, make a statement about what is acceptable today, in modern society. Public history is not, at heart, a historical venue; it is a modern venue that deals with modern issues by referencing, resurrecting, and dismantling the past as necessary.

Hope and Fear in History

“‘Hope’ struck me an overrated force in human history. ‘Fear’ did not.” — Ta-Nehisi Coates, Hope and the Historian, for The Atlantic.

I wholeheartedly agree with Coates on this topic. Many of the historical works that I have read focus around some manner of hopeful conclusion. Even the book on the slave rebellion, which I mentioned in my last post, resolved the ramifications of the conflict in a positive way, despite the rebellion being put down quickly, violently, and with little semblance of justice. It ended on a “sure, everyone died, but things in Parliament got better eventually!” note.

On the other hand, it is rare to see a historical investigation into a topic where things don’t “get better” and the matter is not resolved. One wonders what happens to all of those topics, the ones in which the heroes lose, in which no hope is found. I feel that it is just as important, if not moreso, to search out those histories. Yes, it is important — nay, vital — to the overall historical narrative to resurrect those stories to which history has turned a blind eye. I would argue that it is just as vital to learn from them. What went wrong? Why did this situation go so badly, when others were successful? What does it tell us about the world then, as well as the world now?

Everyone wants a hero. Everyone roots for the underdog to win. Having your protagonist (for retelling history has much in common with literature) lose a hopeless fight is not marketable and, often, one then wonders what impact the losers could have had. Why read about people who failed to make their desired impact? Because their story is part of history, just the same as everyone else. A vital part. A piece of the puzzle. They acted, and were acted upon, within the historical frame. Neglecting them leaves a hole in the image, a silhouette of void that cannot be understood or explained, a forgotten variable in the equation that changes the answer unpredictably. Without understanding this story of hopelessness, one which is arguably far more prevalent than that of hope and successful heroes, one cannot understand the historical narrative or how it led to our current situations. How can one understand, as far as one could, the fear underlying and driving a successful slave rebellion if one does not know the stories of the failed rebellions preceding it?

Add Women and Stir?

Historian Michelle Moravec, our neighbor at Rosemont, has made public a presentation she gave last week on women’s history and Wikipedia. Who is a notable woman? Read more:

The Never-Ending Night of Wikipedia’s Notability Woman Problem

I post this not only because of our recent meeting with Jami Mathewson of the Wiki Edu Foundation but because of this nagging question I have about Ebony and Ivy — which you may have heard if you saw me at the Community Day of Learning last Tuesday. What would it look like to take seriously women’s and gender history in campus histories? Can campus histories be intersectional? [I think you know one part of my answer, or, why I find Dean Spade’s BCRW talk an important intervention.]

More in class!

Education: One of the Master’s Tools Or the Great Equalizer?

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” — Audre Lorde

I was fortunate enough, by complete accident, to purchase a copy of “Ebony & Ivy” in which someone had not only underlined key points, but made several insightful comments in the margins. At the top of page 136, where Wilder discusses how several slaveholders donated supplies and slave labor to the building of the College of Rhode Island, the previous owner of my copy wrote, “Is the university one of the master’s tools? If so, this presumably represents an exception to Lorde’s famous assertion…”

On the Community Day of Learning, during the opening session, I engaged in conversation with a staff member and a faculty member. As we talked about class, both asserted the idea, that I’ve heard time and time again, that education is the “great equalizer” — that the goal is to get everyone access to the same quality of education, because once everyone can attend an elite educational institution like, say, Bryn Mawr, they will automatically have access to equal opportunities and therefore equality will be attained.

There are, of course, myriad problems with this view of education as the automatic route to equality. In a session I helped facilitate for the Community Day of Learning, on cultural, social, and symbolic capital, we explored how, even when students from marginalized groups gain access to a place like Bryn Mawr, they are often unable to attain the same opportunities as their peers from more privileged backgrounds because they don’t possess the knowledge, connections, and ways of being that, while never explicitly taught at Bryn Mawr, are required to gain access to many opportunities that are supposedly open to all.

There are of course many more reasons why education does not serve as a great equalizer, but I think Wilder, in “Ebony & Ivy”, introduces one that I hadn’t fully considered before — that higher education in America was a racist project, built upon slave labor and meant to sustain white superiority through the production of a body of “knowledge” that claimed to justify white domination. A quote from “Ebony & Ivy” that really stuck with me, from page 182, is: “Atlantic intellectuals operated under social and economic constraints that limited and distorted the knowable.” Thomas Kuhn, in his book “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions”, argues that the production of scientific knowledge is cyclical — knowledge is produced within a paradigm until enough evidence builds up to overthrow that paradigm, and then there is a scientific revolution and a new paradigm, that incorporates the new “facts” but is likely incomplete in other ways, comes into being. Since knowledge produced in the early years of the American academy came into being in a paradigm of white supremacy, evidence or facts that contradicted that paradigm were literally unknowable. Even though our scientific and academic endeavors don’t operate in the same paradigm now (although that obviously doesn’t mean we’ve overthrown white supremacy, in the natural sciences or anywhere else; it just looks somewhat different), everything we have now in American academia — not only the buildings and the wealth, but the knowledge itself — is founded upon the ideology of white supremacy. How can something that is both built by the master’s tools and one of the master’s tools itself ever be the “great equalizer” that we, at an elite academic institution that prides itself on being “liberal” and “diverse”, so desperately want to believe it is?

I want to believe that there is hope for academia, that there is a way to revolutionize and radicalize this fundamentally racist project, but reading “Ebony & Ivy” gives me yet more evidence that this hope is probably misplaced. I don’t think I’m going to give up hoping though, and I wouldn’t want to. We need to walk a thin line between not hoping too much, lest we ignore all of the structural injustices impeding progress, and hoping just enough, so that we are spurred to join with our communities to work for equality. Universities likely can’t be made places of justice but, as long as we think there’s even the slightest possibility of that future, at least we will continue to be motivated to change them.

Sins of the Past

At what point can a society or organization recover from its past mistakes and cease needing to dwell on and apologize for them, specifically within historical projects?

Historical projects, whether they be academic writings or public exhibits, can easily become bogged down in the “mandatory” treatment of topics that border or directly pertain to race, religion, gender, or sexuality, to name just a few. Nearly any Western European/American (including North, Central, and South, here) historical topic set in the 18th and 19th centuries must have the obligatory chapter discussing the horrors perpetrated against slaves and indigenous peoples, lest they be called out for ignoring or denying that such issues existed. Yes, it happened. It was the 1700s and 1800s. No, it wasn’t right. Now, what were you saying about missionaries again? Can we get back to the topic at hand?

Let me emphasize here: I do not condone silencing minority histories. I do not condone the actions taken that are now considered reprehensible. I simply am challenging at what point such issues become common knowledge and understanding, that we, as historians, can move past the mistakes of a society and organization and focus on the topic we wish to discuss.

This specifically came to me as I began Ebony and Ivy. I was immediately accosted with pages full of the demonization of white American culture during the early 1800s. I often had to step back and remind myself that the book actually intended to discuss how elite higher education was/is connected to racism and slavery. At the same time, for a different class, I am reading a book discussing the role of missionaries within a slave rebellion in Demarara (now Guyana) during 1823. The same social and cultural issues were discussed and acknowledged, but in a far less aggressive way and in one that pertained to the topic at hand.

Regarding public historical works, the line is far more gray. It is more difficult to discern what would be considered common knowledge among the public at large. However, the same issue can be even more pressing, what with limited space, funding, and attention spans: At what point can the sins of the past be understood as part of the cultural picture (albeit an ugly part) that makes up the world within which the topic inhabits? Being obligated to focus on well-known social issues that border, or even are ancillary to, the historical topic mandates extra space, cost, and time within the exhibit. The loss of any or all of these may do a disservice to the efficacy of the exhibit.

On a separate note, I am beginning to intimately understand the public historian’s struggle regarding communicating with the wider community: It is intensely difficult and stressful to express one’s own take on a situation, let alone a highly-charged historical issue, to a community in a way that will be understood and not taken as an affront. In fact, if one tries too hard to avoid raising the ire of the community, nothing ever gets said or done. If one does not, and the community is angered, very little also gets done, as the flow turns against the historian in question.

Women of Summer and the Philippines

The bulk of the documentary was interesting, though difficult to follow. I was wholly unaware of the summer school program and was intrigued to learn about it.

What upset me, however, was the portrayal of the school one alumni founded in the Philippines. Much of the documentary was forward-thinking and culturally accurate (or, at least, open-minded.) That is, right up until they whipped out the White Man’s Burden and followed that alum to the Philippines where she founded a school in her husband’s home town and educated all the poor Filipino children. Singing was a constant theme throughout the documentary, identified with Bryn Mawr and their revolutionary activities. What is the first thing we see the children doing? Singing, as if the alum brought that cultural aspect to them and they are being raised enriched with Bryn Mawr ideals.

Nope. Singing, especially by school children, is a huge aspect of Filipino culture. They have parades, showcases, competitions, celebrations, and a variety of other opportunities to sing, dance, and perform. My father recently visited a good friend of his in Cebu and was able to catch the Sinulog Festival; he was taken aback by the skill, passion, and artistry of school children performing for the festival. (The closest American parallel might be marching band competitions.)

I was dismayed by the sudden paternalistic shift, as the documentary followed the specific alum to the Philippines. NOTE: I do not intend to characterize her work as paternalistic or colonialistic. What little we know about her specific attitudes and intents seems well directed. I am, instead, calling out the work of the film’s production team and the choices made that cast her work in such a light. Perhaps it was an accurate portrayal, but I would hope to think not.

The ideological content of worker’s education

I had previously learned about the Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers, first when working on a disorientation guide with the Environmental Justice League my freshman year, and next in the biography of Rose Pesotta, an anarchist feminist garment workers organizer, who attended the school. Yet, even after reading the digital exhibit, I had no idea of the politics of the school, or “worker’s education” in general. Was it a creation of liberals attempting to groom women workers to work for reform instead of revolution, a charitable project, or an accidentally or purposefully radicalizing force, or a combination? As Hilda Smith noted, the phrase “worker’s education” scared many conservatives and even liberals. This is probably because it bears a striking resemblance to “political education”, what leftists called education meant to build class consciousness and propel revolutionary action. Some radicals, like the members of the Industrial Workers of the World, even believed that workers had to learn so that they could take over the factories, and the larger society, themselves. The 1930s proved an interesting period for the labor movement and radicals, as the country was pushed to the brink of revolution and the powers that be finally gave into some degree of reform. One can read FDR’s own letters for evidence of the general motivation to save capitalism from itself. With a place at the bargaining table, radical ideas seeped into the mainstream. The Bryn Mawr school seems like a good example of this. Before entering the school, many women were more antagonistic towards bosses and the bourgeoisie, but to their surprise the school incorporated a variety of ideas and values into the curriculum, mitigating some of these antagonisms. For example, Jennie Silverman wanted to start a Marxist study group, and then it became a class, part of a capitalist institution instead of working against it. On the other hand, the school provided women with new knowledge, often focused on labor issues, that propelled their organizing. Some, like Rose Pesotta for instance, did not become liberals and stayed firm revolutionaries. Ultimately the coalition between liberalism and radicalism could not last, as evidenced by Bryn Mawr ending the school after police brutality towards its students observing the 1934 Seabrook Strike.

One interesting aspect of the project was the role of race. M Carey Thomas urged Hilda Worthington Smith not to admit black women while admiring the concept of education women workers, perhaps because she envisioned the working class, and women workers, as white, and saw racial justice and equality for white women as mutually exclusive. This reminds me of the argument that the working class was constructed based on whiteness and through exclusion. This is one reason why the seemingly inclusive environment at the school is especially interesting. The school periodicals even published abolitionist poetry, and one poem in the documentary even addressed racism within labor unions. It seems like the school really represented one related important socialist principle, internationalism. The documentary even discussed how it was organized into multiple sections, each containing workers from different places and industries. This reminds me of the IWW’s idea of “one big union” and a larger trend towards internationalism during this period. This was also relevant to the liberal feminism that surely influenced women like M Carey Thomas and Hilda Smith, as many feminists used the idea of a common bond between women to campaign against everything from child labor to war. Yet, this often discluded women of color, especially black women.

“Bryn Mawr: Hotbed of Radicalism”

When watching The Women of Summer, one of the most surprising things was learning about how Bryn Mawr was on the forefront of a progressive social movement. I was especially shocked when one alum of the Summer School mentioned how a Philadelphia newspaper had claimed Bryn Mawr was a “hotbed of radicalism”, since that isn’t how I perceive Bryn Mawr’s reputation at all.

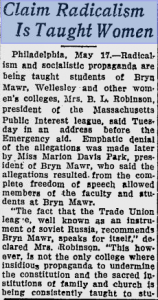

I googled Bryn Mawr and “hotbed of radicalism” to see if I could quickly find the article that the women had referenced. I didn’t find that one in particular, but I did find this article from the Evening Independent of St. Petersburg, Florida from May 17th, 1923, which I’ve screen capped below:

(found on Google News, who made it incredibly easy to find a relevant newspaper headline from 93 years ago online.)

The entire story of the the Summer School for Women Workers in Industry was fascinating, but I was especially interested in the way that it was understood with its political context. The Evening Independent article doesn’t specifically mention the Summer School, but it does hint at Bryn Mawr’s progressive reputation in the 20s and fears about union organizing. the claim of a direct connection between Bryn Mawr and Soviet Russia through the Trade Union League seems ridiculous, but it’s fascinating to think that the Summer School was radical enough to warrant that type of publicity.

Both the quote from Women of Summer and this article mention how Bryn Mawr publicly denied allegations of radicalism. The woman interviewed in the film mentioned how the school administration was angry about the “hotbed of radicalism” headline, and this article quotes a response from Marion Davis Park. Although Bryn Mawr may have been on the cutting edge, their public responses also show the way that the school was still invested in maintaining a reputation that was not tied to radicalism. The school’s response is another integral part of the story, which speaks to the various voices within the school as well as the potential difference between private goals and public image.

Bryn Mawr’s Summer School: Answers and Questions

Before engaging with the documentary and readings for this week’s class, I don’t believe I had any real awareness of Bryn Mawr’s summer school for women workers in industry. I had seen the blue historical sign up next to admissions–probably most of us have–and had read it, but the sign failed to impress upon me the full importance and legacy of the summer school. The documentary and readings on the summer school answered a lot of questions I didn’t even know I had about how the summer school was formed, what students’ and faculty members’ lives were like at the summer school, and the events that led to its closing. However, now that I’ve learned far more about the summer school than what one historical sign could ever tell, I find myself with yet more questions.

First, I wonder about the lives of maids and servants at Bryn Mawr’s summer school. I can count on one hand the number of things I learned about their lives from this week’s materials–they didn’t have to make summer school students’ beds or serve them food like they would have for year-round students, and the summer school students one year demanded that the maids receive better living quarters because they were living on the top floors of dorms, which were (and continue to be) notoriously hot. I wanted to know, firstly, how the administration responded to that request, but I don’t believe the documentary or readings provided an answer. More generally, I found myself frustrated that, when given materials aimed at uncovering silences in Bryn Mawr’s history in a course dedicated in part to exploring uncovering silences, only some silences were finally given voice. Was there so little material on maids and servants because that material doesn’t exist in any archives? Are we just not trying hard enough to find that material? Why, when so many former summer school students and faculty came together for a reunion and were interviewed about their experiences, did they barely discuss the roles maids and servants played? Did they talk about this subject more, but the interviews weren’t included in the documentary? Why was only one former summer school maid interviewed, and only given about 5 seconds of screen time? How were the summer school maids and servants hired? Did they also work at Bryn Mawr year-round? If making students’ beds and serving them in the dining halls weren’t their responsibilities, what were? Did they do work similar to what our housekeepers do today? I suppose the best way to answer some of my questions might be to go into the archives myself, to do my best to uncover these silences, but it saddens me that the people who have already undertaken efforts to tell the stories of Bryn Mawr’s summer school seemed to have relatively little concern for the lives of maids and servants there.

Second, I was struck, in the documentary, by the singing of Bread and Roses juxtaposed with the strikes and demonstrations Bryn Mawr summer school students and faculty participated in. Ever since learning the history of Bread and Roses as a song of the labor movement, I’ve felt somewhat uncomfortable singing it at Step Sing, as if we have appropriated this song, largely ignorant of the decades of labor organizing behind it, as a recognition of the culmination of our college lives, so different from the lives of the women whose experiences are told in the song. However, I don’t know when, or why, Bread and Roses became the senior song at step sings. Watching “The Women of Summer” made me wonder if it somehow came to Bryn Mawr through the summer school students and their labor activism? If this were true, I would feel, when I sing Bread and Roses at step sing, that at least I am calling on a history of students here, consciously remembering and celebrating their struggles. But of course most students still would sing the song not knowing about the summer school, and I wish more people knew about the powerful organizing in which summer school students and faculty (and maids and servants? Again, we don’t know) engaged.