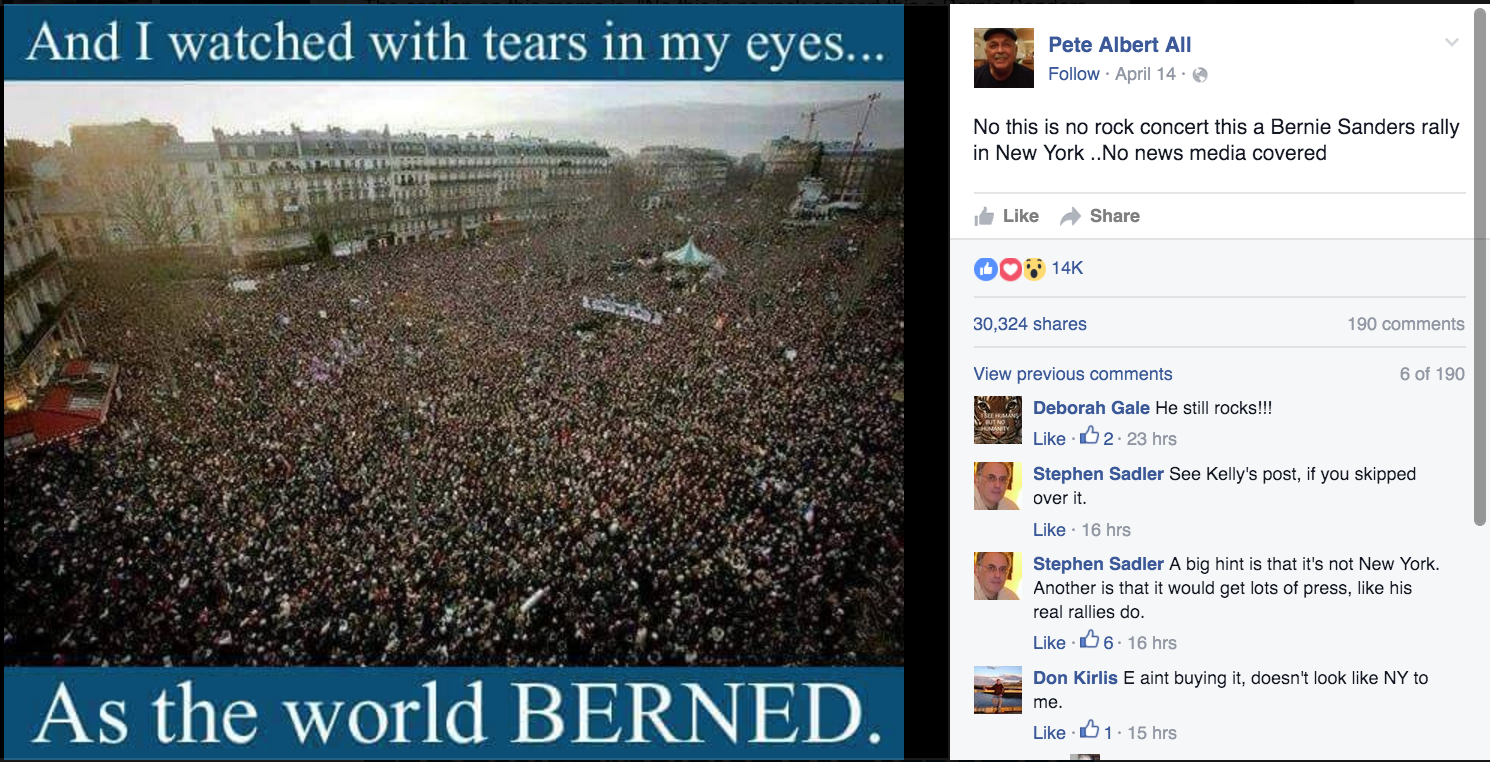

I know this is blog is later than necessary but before we met I wanted to get some thoughts out. At first I thought this weeks readings were disconnected and struggled to draw clear conclusions between them. I spent a few days thinking about Fred Wilson’s exhibit and was hit with an answer finally when scrolling through my facebook feed I saw this:

The caption reads “No this is not a rock concert, this is a Bernie Sander’s rally in New York & no media coverage”.

This is not New York, this is Paris. More specifically this is Place de la Republique on the day two million people gathered together after the Charlie Hebdo attacks. Place de la Republique is also where the November attacks took place and the central statue in upper left corner of the picture has functioned for over a year as a memorial to the victims of these attacks. Just past the statue is my partner’s apartment where he (and I on FT) listened to the sounds of terror that November night. When I last visited Paris a few weeks ago, I saw the physical transformation of the square from a place of community into a quiet place of shared grief. How does this relate to archives & public history? I’m getting there, bear with me.

Around the monument were tons of pictures, cards, drawings, poems, and biographies of the victims. The sight was so harrowing for me that I couldn’t speak let alone take a picture. The stories of the Parisians whos grief I share and who could have been my love were overwhelming and I felt them. While laying my rose at her feet, I asked my partner what was to become of all of these things, who does this memorial belong to? Without blinking he said “to the Paris archives of course”. And with that, my fears were calmed and my raw emotion was transformed into a history that I felt was going to be kept safe.

So back to Bernie (or really his supporters)… when I saw this picture I was struck with pain and anger. How dare someone take an image of shared grief and appropriate it to fit a narrative of cultural & societal erasure? I was so hurt and so was Salman. He was shaking his head and I was trying to reason with the uncontrollable hurt but I when I closed my eyes all I could see was Wilson’s whipping post and chairs. I immediately realized that what hurt so much was that I had transformed my own personal pain into a manageable burn by thinking of it as a shared, safely kept history. I soon realized that all the readings this week have to do with emotion. The emotion that Wilson felt curating, the emotions he aimed to illicit by illuminating pain that was never safely kept or allowed to be shared, even the emotional connection that Thigpen created with Mary by guarding her personal history and telling her story.

Though I still dont have concrete ideas about what academic conclusions I can draw from the readings, I am certainly happy I was able to contextualize the pain from that meme and realize how minimal my experience of erasure was in comparison to the thousands of years other’s have had to endure in silence.