My project is inspired by a lot of the work that I do with *the college news* and I hope to use the issue of the current office space in the Pagoda to understand the history and presence of the newspaper and other “extra-curricular” student services at Bryn Mawr. I’m envisioning that my project will have a few different legs: 1) the history of *the college news*, 2) the newspaper’s online presence, 3) the physical space of the Pagoda and the editor’s interactions with administrators to hold onto that space. I’m hoping that the project will help think through saving, the issue of being semi-private and semi-public in our publication, and the power of narratives and story-telling for the teller and the community.

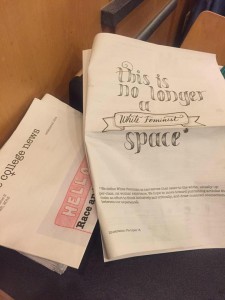

I started to think about this in terms of space because the college news has been having a hard time getting a permanent space on campus that can be our office. I know that other colleges have permanent rooms for their newspaper staff, so it seems odd to me that it’s so difficult to make that happen here. It makes me think that if it takes so much for a school newspaper—which plays such an important role in marketing the campus and capturing what kind of community we are—to get an office, that something about the foundations of the school doesn’t care about student spaces and student life.

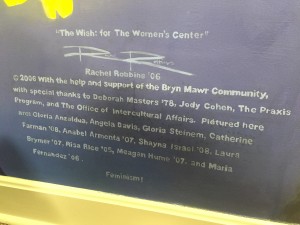

Further, thinking about space is important because I’ve been wondering about how spaces structure affect, which I saw us discuss a lot in this class. I see my project in conversation with Erika Doss’s project Memorial Mania: Public Feeling in America. Doss sees an obsession with memorializing, and thinks about how memorials structure public feeling, and functions as a focal point of community building. I see *the college news*, particularly because it is a feminist newspaper and so connected to lived experience, as similar to memorials.

I’ve also been thinking about the online presence of *the college news* in terms of Take Back the Archive. When I was on the train once working on “the secrets issue,” the man across from me asked what I was working on, and when I told him he asked where he could find my article. I told him: nowhere. As far as the outside world is concerned, *the college news* doesn’t really exist. This is good in some ways–we can tailor our content, we don’t need to explain or define certain terms or traditions for the most part, and when students write very personal things relating to gender or sexuality or trauma, we can offer them a certain degree of protection. However, I wonder if we’re limiting our potential for connecting with others outside our community or our ability to save content. It seems to me that Purdom Linblad is grappling with a similar problem, and her approach has been similar to ours: move slowly.

As I said, my project has a few different legs, but my hope is that thinking about *the college news* will help Bryn Mawr students and community members think about the semi-open and semi-private nature of the college itself. In the few years I’ve been here, I’ve seen Bryn Mawr students struggle to identify with other undergraduates at peer institutions. I’ve been in rooms with people who see strong similarities between our experiences at Bryn Mawr and other students, but Bryn Mawr seems to be cloistered in multiple ways. We aren’t on the national stage in the same way that other Seven Sisters are, and I wonder to what extent the architecture of the college and its mission are in relationship with that separation. I see the newspaper as an example or case study of this tension.