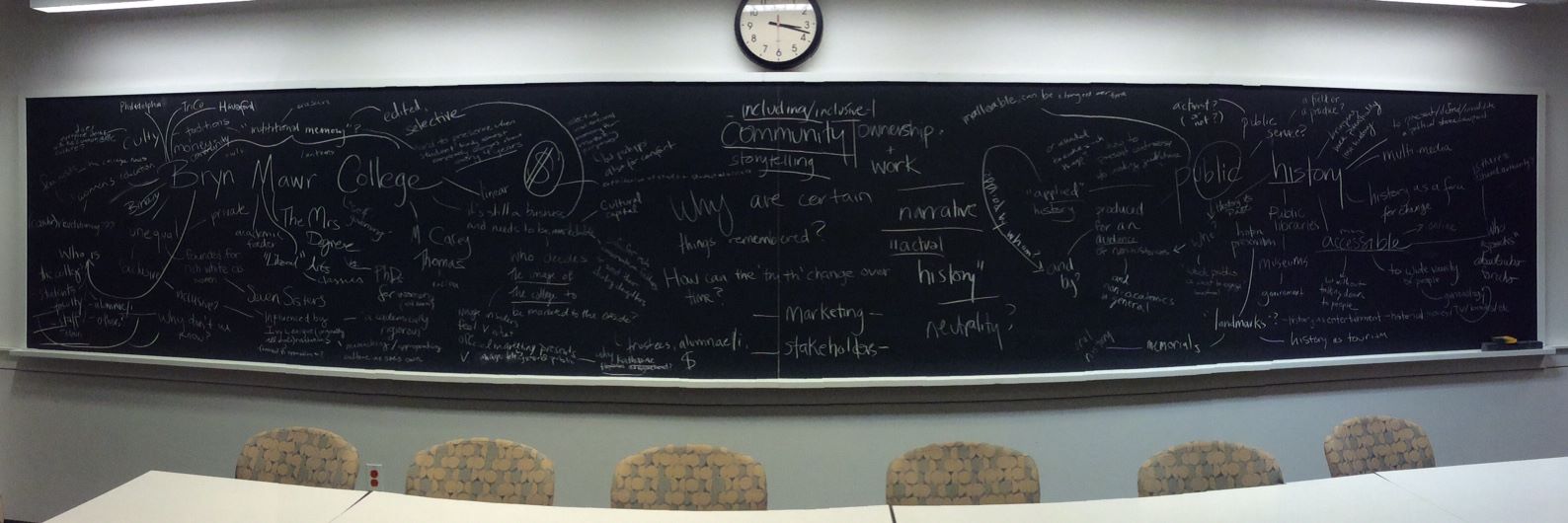

As a student, who is deemed worthy enough to be preserved in Bryn Mawr’s institutional memory? Which alumnae/i does the college actively try to present and represent in its promotional materials, on campus, around the world? These are questions that I’ve been grappling with ever since my first to Bryn Mawr’s campus as a prospective student. If I think back to this class’s first discussion, I know I’m not the only one thinking about these questions either. On the Bryn Mawr concept board that was made during our first class, someone wrote the name “Katherine Hepburn” and a question was brought up in class asking why Katherine Hepburn had been chosen as the alumna of the college — the “it girl”, our purportedly most famous graduate? Who decided that she was the person who would draw in students as opposed to Marianne Moore or Emily Balch? Was it the College’s administration, or maybe the Board of Trustees? Perhaps it was a public relations company who measured the “Q Score” — the familiarity and appeal of a celebrity, brand, or entertainment product — of Bryn Mawr’s alums and decided that she had the highest score, making her the most recognizable. The diverse array of tactics that could’ve been used to determine who Bryn Mawr should showcase are a mystery, at least to most students.

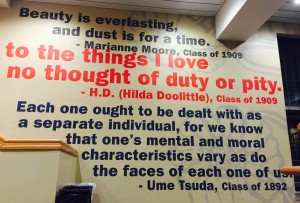

Earlier in the week, I decided to get some work done in the mezzanine (loft area) of Bryn Mawr’s Campus Center and found myself staring at a quote on the wall that I had passed numerous times in my past two years at Bryn Mawr. It read:

“Each one ought to be dealt with as a separate individual, for we know that one’s mental and moral characteristics vary as do the faces of each one of us.” — Ume Tsuda, Class of 1892

There in front of me beamed the quote of a student who we had just studied in class. Though Ume Tsuda has never been widely mentioned on Bryn Mawr’s campus, her presence is here even if it’s hiding in plain sight. As we read in Daughters of the Samurai, M. Carey Thomas took a liking to Ms. Tsuda, making sure to keep an eye on the College’s first Japanese student, and personally taking it upon herself to guide and mentor her. From a quick Google search I can see that Bryn Mawr’s website has posted a couple of informative posts about Ms. Tsuda over the years, highlighting in particular how she was inspired by Bryn Mawr to found her own women’s college in Japan.

http://about.blogs.brynmawr.edu/ume-tsuda/

http://www.brynmawr.edu/alumnae/bulletin/tsuda.htm

Keeping this in mind, I once again ask the question, who gets displayed and showcased as a part of Bryn Mawr’s public history? Ume Tsuda was a “first”, but so was Enid Cook. Many of the upper middle class Black women who attended Bryn Mawr from the early 20th century up to the 1960s arguably reflected the values of the College just as much if not more than a visiting international student during that time period. Linda Perkins’ “The Early History of African American Women in the Seven Sister Colleges, 1880-1960” is the first time I’ve ever heard of these women though, many of whom went on to pursue illustrious careers while their White peers decided to become homemakers.

It’s the wild success stories, the alums who got a Bryn Mawr degree without too many bumps in the road and without too much controversy that the College has chosen to cherish in the past. The ones who can be exotified or perhaps even deified. The College has recently taken a step in a new direction in terms of which alumnae/i it chooses to represent. It was revealed that the former Perry House was renamed the Enid Cook Center ’31 during an opening ceremony this past Fall. By many, it was seen as a public acknowledgment of the College’s first Black graduate, and by some, as a decades late apology for the exclusionary housing policies that prevented Ms. Cook from residing on campus during her time at Bryn Mawr. Currently, there is a petition to rename Thomas Great Hall (TGH), formerly known as M. Carey Thomas library, due in part to the former president’s explicit eugenicist beliefs.

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/154Oq3K-heskHzvICsr6xpVAbbeYxpweEo53ddl3LBiU/viewform?c=0&w=1

If Bryn Mawr chooses to act on the petition and change the name of TGH, this could signal a new era of public history and the representative image of Bryn Mawr College. Not only would the College be bringing further attention to its less than spotless past, it would also be giving current students agency in determining who gets represented in Bryn Mawr’s public history.